|

| Beginning visit with Valley Oak |

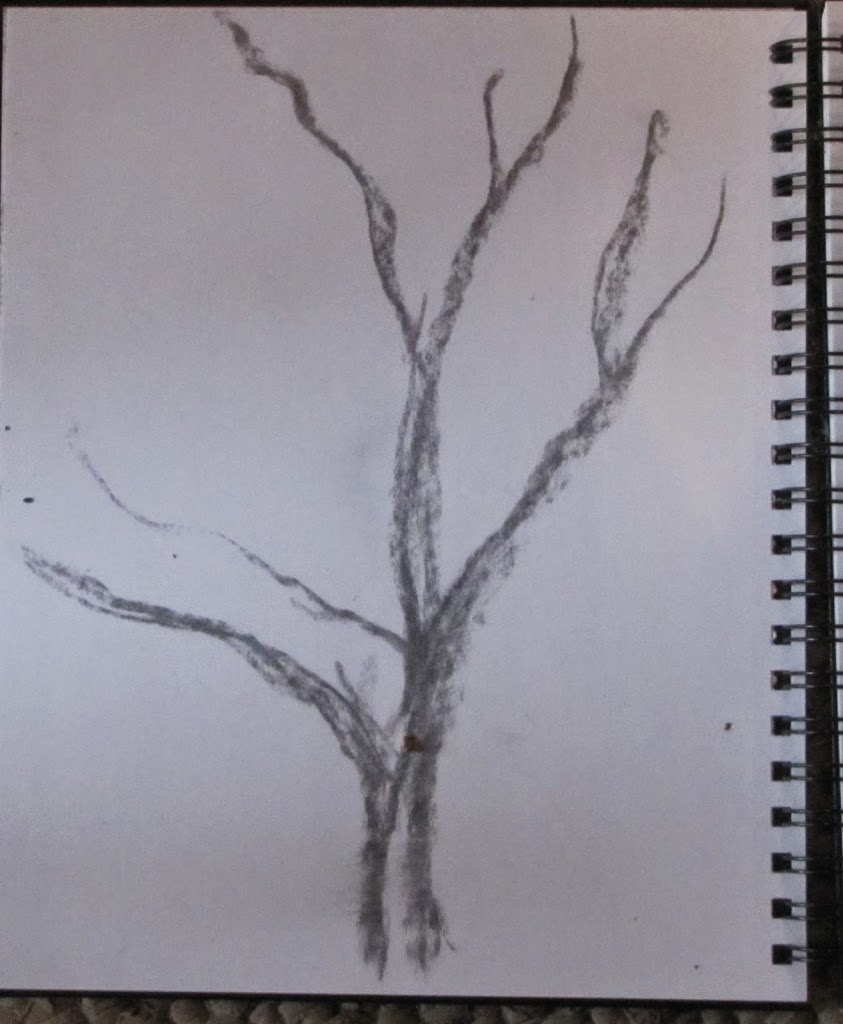

The method is simple: suspend rational thought, forget what you think you know about what you are seeing, lay down the mantle of ownership. Simply be. With your hand— or in your mind’s eye— draw the plant. Get every detail: the way the leaf curls inward on the edges, the way the sturdy short stalk bears a bud. Or the flow of the graceful curve of Valley Oak, its branches stretching upward and out, like antlers. Let go of ambition to preform, of judgement of

what appears. This is not art, this is communication.

Simple, and yet, like all meditation, full of the rigors of discipline! Part of me whines! Too much to do to take time to sit down, to draw! Still, I settle into that state of mind that hears the hum of bees, the back and forth discussion of barn swallows, the interruption of excited calls of red tail hawks. It is of one piece, and in this state, I know my place.

“We ought to talk less and draw more,” Goethe stated. “I, personally, should like to renounce speech altogether, and like organic nature, communicate everything I have to say in sketches.” (IX, Italian Journeys.)

Is image the language of organic nature, a language we ignore? Is farming learning this language again, and only then, combining it with our thinking about image perceived? What new consciousness comes?