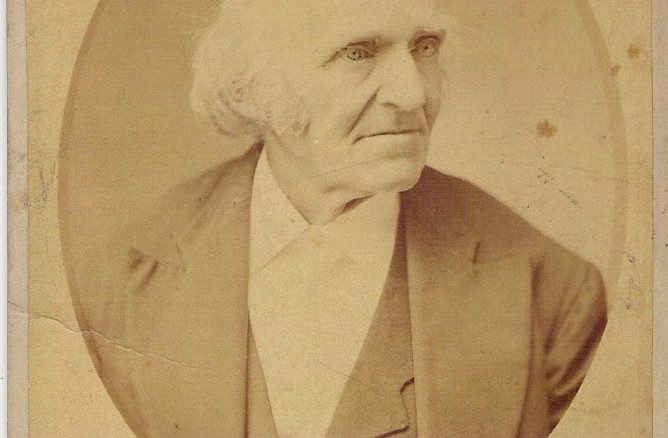

| My Great-great Grandfather, William Starr Peabody |

In Celebration of Lughnasa: Family Stories About The History of Old Stonington Colony, Part One

In celebration of the harvest festival of Irish Lughnasa, or the English Lamas, I want honor some my own farming ancestors.

The following is from my mother’s father’s side, the Peabody’s, who, in the mid 1830’s, contracted with a group of 60 families in Stonington, Connecticut, to establish a colony in central Illinois to be known as the Old Stonington Colony. My great great grandfather Captain William Starr Peabody, a carpenter, was among this group.

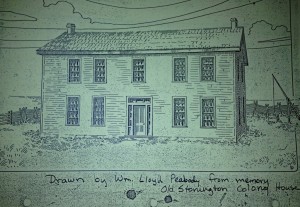

The land they bought and occupied ($1.25 per acre) is gently rolling, still farmland, and has always felt mysterious to me, being not particularly easy to find. It has that kind of Avalon feel! The original group had the land surveyed for a city even before they arrived, planning for a Baptist church and about five hundred city lots, all organized around a town square. There were even plans for a college, to be named Brush College. A two story colony house was built by my Great-great Grandfather in which families could live until they built their own homes on surrounding land, and I believe that this later became his own home.

|

| Drawing of the Colony house built by William Starr Peabody and drawn from memory by my grandfather William Lloyd Peabody |

However, things did not go as planned. When the first group from the colony arrived in Illinois and got a surveyor to lay out the city that had been planned in Connecticut, they discovered the city’s location was a 30 to 40 acre lake and “deep enough to swim a horse” so the city was moved two miles south. Then some of the potential city lots had to be sold off to finance the colony house. (My great uncle Guy Peabody (b. 1878) said that when his father, my great grandfather, was elected County Treasurer of Christian County, his family moved to the county seat in Taylorville. My great grandfather sold the land, only then discovering that their farm was the location of the imagined city of Stonington. It took some work, a trip to St. Louis, and “quite a sum of money to get it vacated and put back in farmland.”) When the Walbash Railroad went through a few miles to the northwest, the post office, and then the town of Stonington was moved. Nowadays only the cemetery, that secluded last resting place of my great grandparents and many of these settlers, is all that remains of these people’s dreams.

The journals and accounts show life was hard:

Three to six yoke of oxen were hitched to a wooden moulboard plow with a cast iron point that threw a furrow 26 inches wide. After the ground was first plowed, it took three years for the prairie grass roots to rot.

My great grandfather and N.B. Chapman, who was nine when his family moved to the colony house, recounted the following:

Game was plentiful. Often a man would appear at your door and offer to sell you a saddle of venison, stating that though he did not have it he was on his way now to kill it. Wild turkeys were in abundance, and hunters would sell you a 25 pound turkey for 25 cents. The breasts of the turkeys were salted down and dried and used in the summer somewhat as we use salt fish. Other game such as ducks and geese were abundant as were prairie chickens. Of course there were wild things not so pleasant, such as wolves and Indians. Indians I think usually were harmless, but the wolves would attack the stock.

And clothing was something the women had to learn to make from scratch:

Getting things to wear was as difficult as getting them to eat. Like all the pioneers they made use of the skins of wild beasts. They early raised sheep and the women learned to spin and weave (if they did not already know how). The wool was taken to Springfield 35 miles away and carded, and then the women made it into yarn from which they made it into socks and stockings and likely other garments. Then they began to raise flax hackle, mixed the threads with cotton and would weave it into cloth from which their garments were made.

As rough as life was these first years, my relatives loved to tell stories, and these stories are also included in these accounts. Here is a section in the accounts called “incidents.” (Throughout their writings they love to talk about “incidents!”)

Here is one [incident] that I heard my father tell.

One day a man from over in Mt. Auburn Township came riding across the prairie and arrived at the Colony house, his horse all in a lather. Grandfather Chapman met him out in the yard and the rider said, “What did you do for your horse when it got snake bit and took lockjaw?”

“Why,” said Grandfather, “I just drenched it with a pint of whiskey.”

The man turned and rode away as fast as he had come. They did not meet for many months, and then the man said to Grandfather, “It was funny about my horse. I drenched him with the pint of whiskey and he just stuck out his legs and was dead in a minute.”

“Well,” said Grandfather, “that is the way it affected my horse too, but all you asked me was what we did for it.”

These stories reflect the resilience of spirit in these ancestors. Storytelling and humor carried them through periods of almost insurmountable hardships.