What do we truly understand about falling in love? Some say it’s like a lightning strike, but to me, it feels less sharp. It’s as if everything melts into a warm, radiant sphere of presence that expands our hearts beyond what we knew. Suddenly, reason, if it remains at all, is infused with an essence beyond time. Any plans we might have held are gone, leaving our legs weak and our solar plexus punched—except when we’re with the Beloved. Then, we vanish for a while, merging with that comforting joy of timelessness. I am certain that when I die, this will be what heaven is like.

I can count on one hand (oh, maybe two!) the times I’ve fallen in love: the first time I met my college boyfriend, the birth of my sons, the first time I met Bruce as he was walking down the sidewalk in Graton, waving shyly.

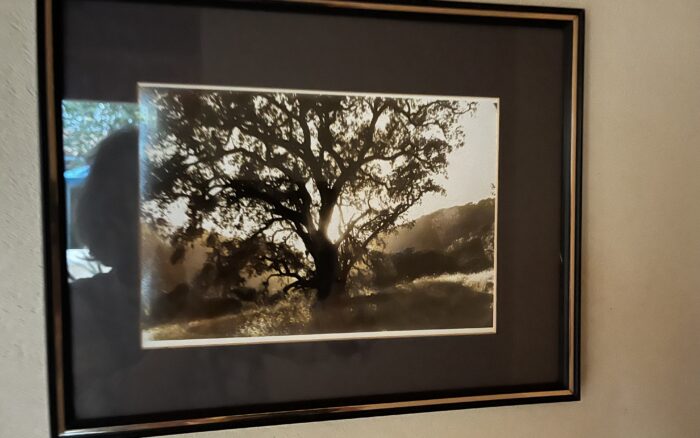

And then there’s the time I first met the Valley Oaks on our ranch. I’ve shared stories of my love affair with oaks before, and I won’t repeat them here. But suffice it to say, when I first encountered the Valley Oaks, I was smitten: the giant 250-year-old oak that sheltered the small pioneer farmhouse where Donald and I lived while building our home up the mountain, the enormous valley oak in the vineyard under which we were married. Then there’s the oak savanna, which knocked me to my knees the first time I entered. I knew this was where I wanted to spend my days. We placed our house using two sentinel oaks standing side by side, overlooking the grasslands of the savanna beyond.

Fruits of Eden: Field Notes: Napa County 1991-2021 was inspired by my efforts to protect that savanna from development. In fact, oaks have inspired much of my writing: the article which started with a phone call from Ramon that the ancient oak near the little house had fallen; the day we found the valley oak we were married beneath, lying strangely horizontal beside the vines; and the valley oak in the savanna that offered its leaves, stems, and roots as a homeopathic remedy to heal me from the stress of a particularly rough, initiatory period.

When I first learned that the oak savanna might be developed into a vineyard, I fell into a depression. Only by using my writing to give a voice to the trees could I lift myself out of the dark depths of despair. Just when I thought that this fear for the savanna was easing, a new worry arose for the valley oak. But this time, it’s worse. I first became aware of this threat to the trees last year, when I asked our tree guy Alejandro to trim the lower branches of the valley oak where we held talks and poetry readings during our annual open houses. Rows of lavender fingered out from the shade of the gentle trunk, with the audience sitting in white wooden chairs between the rows. The branches had grown so low that we had to duck to walk underneath.

Within a week of Alejandro’s trimming, I noticed large brown patches high up. We contacted Bill Pramuk, a local arborist, who diagnosed the disease as Mediterranean Oak Borer (MOB, Xyleborus monographus), a European ambrosia beetle that first appeared in Calistoga in 2019. He showed me brown trails of pests in the cut logs. The small insects farm fungi inside the tree by inoculating the sapwood with it. The fungi then kill the tree. Our best chance to save the tree, he told us, was to remove the infected branches and then chip, bury, or burn the wood. We were told to water the tree to a depth of six inches to reduce stress. And there’s no indication this will work. In fact, according to Sonoma County arborist Matt Banchero, “In high-pest-density areas, every elder oak has died, and the spread of MOB is occurring at an exponential rate. Over 3 million acres of California Oak woodland are at risk.”

And so, we had Alejandro amputate great boughs of infected wood from the top (since MOB starts at the top and works its way down), and then we had him return and cut again, and then again. The once lovely, graceful tree is now half her size. Although the lower branches are lush and green, her prognosis remains poor. We are told one option is to wait until the tree wakes from her brief hibernation next spring and inject a pesticide, if the tree survives that long. All treatments are experimental.

Is this threat to the iconic Valley Oak a result of climate change? Almost certainly. Prolonged droughts stress trees, making them more vulnerable to pests. We can water the trees to their drip line to reduce stress, but will this be enough in the end?

We have acted like an invasive species, removing 99% of Napa County’s valley oaks for agricultural development. Now, an ambrosia beetle might finish the job of destroying the Valley Oak. Banchero urges us to protect and plant acorns from oaks that have resisted the borer. Protecting the valley oak is a process filled with guarded hope and grief. Yes, I will gather and plant acorns and hope they have the resistance to move into the future, but I will also remember the trees I loved and still love on our ranch—the ones that shaded our home, our annual open house events, offered altars for weddings, and that still greet me each morning. Because love bears all things.