When I saw the recent missed call on my cell phone, I grew worried. I had just spoken with my sister Judy several hours before. Something must have happened. I didn’t reach her until late in the afternoon. “I received the first payment,” she said. “The farm is gone.”

We knew this was coming. I had encouraged her to sell the house, barns, and acreage she had received in the settlement (the rest of us had sold our portions long before), as none of her children wanted to take the farm and it was deteriorating. Furthermore the buyer was a cousin who really wanted it. It was staying in the family, just in another line.

But today this was no comfort. I remembered scenes from my novel Snakes (were these premonitions?) which turned out to be my own grieving process of the farm. Grief is like that. It simply has to be borne, and my way is often through writing. (How many of us write fictional accounts which later turn out to happen?)

My great grandfather bought the land from an early settler in the middle 1800’s and built the East Lake style farmhouse after a good year. He died in that house, as had his wife and ten year old daughter Della before him, as did my grandfather and grandmother. My father was born in the house and he and my mother lived there after his mother died.

“I think it is the Irish in us,” Judy continued. “Land is an anchor.” And we both sat with the swell of grief for the passing of this anchor.

As I have said before, Snakes is a novel—fiction—with one exception: the farm sale scene. It was my eulogy for the farm we loved. The characters, of course, are different, but it is almost a word for word recounting of that sad day we sold my dead father’s farm equipment. In my own tribute to the sale of our family home, I copy it here. May we each internalize the love we had for every square inch of that land and transfer it to the earth under our feet.

Jimmy decided to sell our family farmland to Marvin Hobbs whose own land abutted the north forty, negotiating what he felt was a fair price. He set a date to sell the farm machinery at public auction in February, a time before spring work began. The notices put in the papers for miles around brought buyers from 200 miles away. “Jim Galway attended many auctions and kept everything,” the notice read. “Something here for everyone!”

These days a farm sale is a funeral of sorts, not only for the farmer who is selling out or has died, but for the continuing of the small farm as well. Everyone who comes knows it. For most, it is only a matter of time until their own farm machinery and land will be up for auction. Each sale, usually a consolidation and the loss of a farming family, leans on the economy of the small town nearby. The main street in Flat Rock is lined with darkened storefront windows, like lost teeth. The Flat Rock schools are now consolidated with Macon’s, our basketball rivals when I was in school, and Flat Rock no longer has a grocery store.

I returned with Kristen the week before to help Jimmy prepare and to be with Mama. Dorothy came too, and although Jimmy really was the one to do the sorting, Dorothy and I helped arrange smaller items on flatbed trailers: wrenches, hammers, shovels, bolts and nails, your wood working tools, chains, grease guns, gear pullers, vices, battery chargers, bench grinders, and antique tools of Gerad’s and his son, our grandfather. We got a dumpster and filled it with the obvious trash, but most of the items would sell.

Meanwhile, Jimmy pulled out the farm machinery and parked it along the driveway and around the cribs: the 1928 “D” John Deere, the 1976 John Deere, the disk, the harrow, the chisel plow, the grain drills and barge wagons, the 500 gallon pull sprayer, trailers: all archaic in this day of industrial farming.

Mama cried easily. She was still living in the house, although she was preparing to move to a small two-bedroom bungalow in town. Jimmy and Kate would move into the farm house. Mama and Jimmy decided to keep the tractor that you bought when you and Mama were first married, which Jimmy would use to farm the acreage we were keeping around the house; we would keep enough implements to do this minimal farming. All of the rest was to be sold.

The morning of the sale, the church ladies arrived at 7 A.M. and set up a coffee and snack stand in the garage. It was overcast and bitterly cold. People began arriving almost as soon as it was light, snug in insulated coveralls, the only dress reasonable in the grey chill, biting winds, and occasional snow flurries. They milled around the barns and examined the stuff on the flatbed trailers, which we had pulled into the implement shed. By the time the auction started at 10 A.M., cars and trucks were parked a quarter of a mile in all four directions, marking the corner of our generational farm. Right here. This is where it was. X marks the spot, if you see it from the air.

You knew the auctioneer well, Brady O’Connor. It was with sympathy that he greeted Mama that morning. Mama was brave, I tell you that! She made two pies for the church ladies to sell, put on her blue parka with the fir hood, and took the pies to the garage. The church ladies greeted us, “Oh, you needn’t have done that!” But they knew that she had to do what she always had done: contribute. They offered us hot chocolate. Then Mama stood with Dorothy and me to watch the auctioneer, linking arms. Occasionally she wiped a tear before it could freeze.

The coveralled buyers averted their eyes, knowing what this meant to us. And we watched as the physical proof of our family history was dispersed: Brady would call out, “Here is a woodworking set, complete, good shape, who will start the bidding? $75? Do I hear-75? 75! Do I hear 80? 85! Okay, 90!” He was fast and pushed the price. “Gone! For $95 to the man in the blue hat!” and he moved to the next item. After the smaller items were auctioned, his auctioneer’s wagon was pulled around the property from implement to implement, from piles of lumber to antique doors, until everything had been auctioned. People carried off 150 years of history, as if it had never happened. Farmers and collectors pulling trailers loaded tractors and antique wagons, augers and grain drillers. By 3 P.M. it was over. Now, like ravens, scrap metal people picked clean all that was left.

As it was growing dark, we sat around our old kitchen table with Brady, and he counted the profits: $40,000. That is what it all added up to. None of us could stop it; it had to go this way. There simply was no other cure. (from Snakes, pp. 137-140)

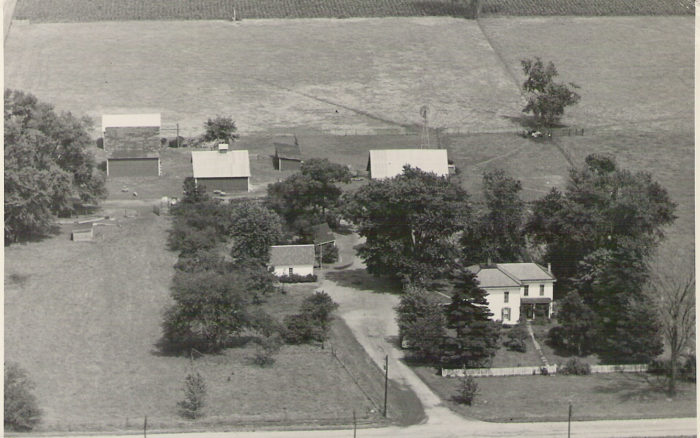

Pope/Damery Family Farm