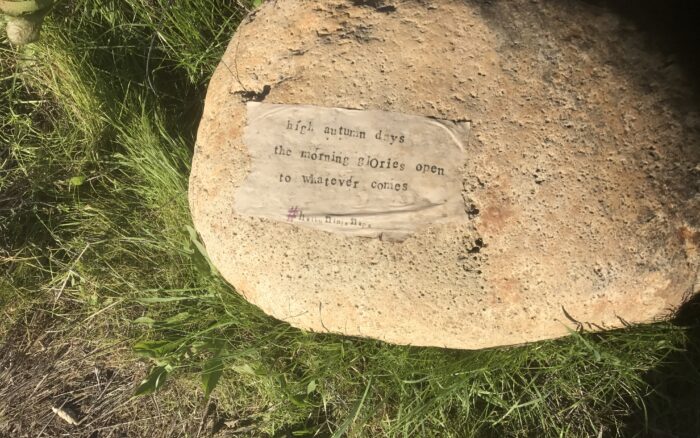

Casey and I ran across the stone one late autumn day in 2016 as we were hiking the trails of Austin Park in Napa. We stopped in surprise, examining a haiku pasted to its side. “grass greens bright/long slow drizzle/ flowers prepare to POP”. We photographed the stone and continued down the trail. Just as we were about to forget it, we ran into a second stone. “dance dance/ dance dance/ little little/ snail snail.” And then a third: “high autumn days/ the morning glories open/ to whatever comes”.

The stones brought mystery in their simpleness. They were the color of the path, the earth embedded within, then studded with words on transparent paper executed by a typewriter, ephemeral and peeling from recent rains.

Those words have stuck with me, more of their fact than anything else. The message feels particularly appropriate for this autumn, this time of pandemic, and civil unrest, and fire.

I finally googled Haiku Ninja Napa. You can do it too. Over the course of 18 months, the artist chose 40 poets and left ninety haikus in 12 locations. She called it a Social Media Experiment. “In the public sphere artwork and arts events may not always be integrated into the local natural environment or relatable to the people who live and work in the community.”

Christo’s Running Fence was another of those kinds of art. For two weeks in September 1976, almost 25 miles of 20-foot high fence made from white parachute fabric traced the land’s undulations through Marin and Sonoma Counties, ending in the sea. The fence ran through Valley Ford, a small community on Route 1 where I lived for a year during grad school. Many of us rode bikes or drove cars, following its course as best we could. A documentary of the planning and installation of the fence attests to its power. Although there was much controversy at the time, Christo and his partner Jeanne-Claude somehow gained the support of the 59 landowners over whose acres it traversed. Ranchers are pretty pragmatic people, and the fact of Christo’s winning them over to have an art installation running through their properties is amazing to any of us who have a rural background. Years later I watched the documentary of the project at the old Monte Rio theater, The Rio. In the winter it was so cold in that theater that you had to bring a blanket. The evening of the showing, the theater was populated by some of the ranchers. In one scene, a rancher tends his sheep, the only sounds being the baaing of the sheep and the wind billowing the parachute fabric. On the upturned rancher’s face is awe.

Art can do that: bring us into the divine beauty of the forces of the present: the wind, the curve of the land, the workings of the elements on rock and word, somehow touching eternity through temporality. Barbara Gonnella, owner of the Union Hotel in Occidental and a rancher’s daughter at the time, says it all. “I was only 17 then,” she said. “I loved living out in the west county. Everybody knew each other, most of the families were from the same region in northern Italy. But when the fence came, I got a sense of something bigger. The way it looked running across the hills, shimmering, changing colors in the light and the wind. … I felt like my heart was going to burst.” Sonoma Magazine,

But Christo’s Fence impacted more than the ranchers. Brian Kahn, a new supervisor in Sonoma County at the time, put it this way. “.. the fence came along just at a point when land-use policy was the primary matter of concern in the county, and it seemed to galvanize emotions on all sides of the issue. In a way I didn’t realize at the time, it focused people on the landscape and the impact our land-use policies would have on the future of the county.” He added, “Through the mid-’70s, the county was focused on — actually divided by — a proposed general plan. It was going to determine whether growth would be contained and orderly, or largely unregulated. The plan finally was adopted in 1978, and I’m convinced the fence was a major factor. It made people think about the land and their relationship to it.”

The staying power of the rock and haiku in my psyche is a testament to this art’s effectiveness. Thank you, artist Gloria Treseder! Will we be able to “sense something bigger” and be informed by such as we move into this next phase in Napa County and our country, a time of change none of us can predict? Will our sensitivity to the land and its needs inform the decisions we make as we navigate the pandemic, the many land-use decisions upon us, now strongly influenced by fire and water security, and the strains of civil unrest and social justice? Will the piercing beauty of the Present open us to the larger picture of the common good and to whatever comes?