|

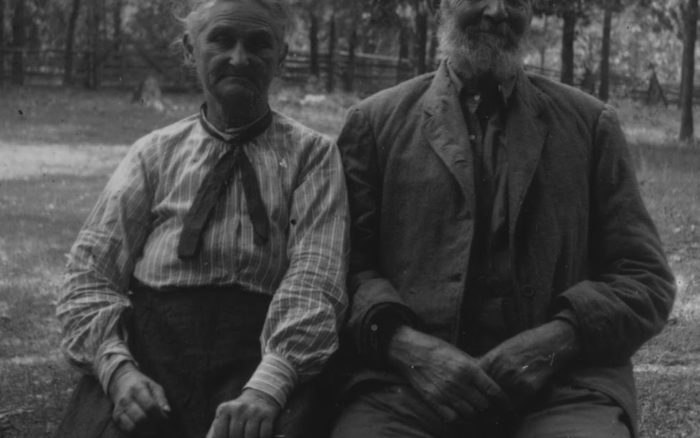

| Farming Couple, about 1900, identity unknown. Photographers, Ed Damery and Mr. Sutman |

Farming and Politics: A Personal Story

Some years ago my oldest son Jesse interviewed my father for a school project. My father lived his entire life on a small Illinois farm. In early years he and his family raised several crops as well as hay for the cattle and sheep. Chickens provided eggs and meat, and the cows, milk. For many years the farm was self-sufficient.

His family was close friends with the neighboring Sutman family. At the turn of the last century, in their wild and wooly days, Mr. Sutman, as he was always called, and my grandfather traveled north into Wisconsin photographing farm families. We still have these photographs which are a record of a unique period in history. For years the Sutmans and the Damerys helped each other whenever needed. After Mr. Sutman died, his unmarried daughter Leona lived in the farmhouse and my father did the farming.

At the time of the interview, Leona had died and her nephew had inherited the property, acquiring a farm manager. My father still did the actual farming, but the manager made the decisions: what to plant and when to harvest. My father was in his 70’s at the time. He knew the land intimately: where it flooded, where the crop would be thin, what areas you could get back into easily after a rain. The land was haunted by memory: the old dirt road (Lover’s Lane) along the eastern boundary where couples once parked; the blackberry bramble that used to be a tennis court; the magnificent, obsolete barns, soon to be torn down to make more ground for corn.

My father lived through death of the small farm as an institution, and then, he lived in its wake, farming until two days before his own death. In the interview he was resigned. He did not know what would happen to the family farm when he died: that would be up to us. He believed that our farm was no longer large enough to be viable financially.

Farmers are fiercely independent, one of the reasons they are often Republicans. Republicans are for less government, more grass-roots control. My father donated enough money to the Republican Party that they were always sending him calendars, the last of these with a picture of a smiling George W. Bush on every month. (My mother said that more than once my father’s and her votes canceled each other out!)

There is a term C. G. Jung used to describe a situation like this: enantiodromia, meaning, when something gets too extreme, it turns into its opposite. Lack of government regulation, still an agenda for Republican politicians, opened the door for corporate control. It began after the Second World War when there was an excess of ammonium nitrate once used for weapons. Farmers were encouraged to use it as an easy, cheap source of nitrogen. In the 70’s the Nixon administration encouraged becoming more efficient through mono-cropping and farming everything: getting rid of hedgerows (where native birds and animals reside), “industrially” farming animals. Barns and sheds and soon farmhouses were no longer needed and torn down and the ground planted as well. Farmers leveraged their land to buy more, grain prices dropped as supply increased, and many farmers lost their shirts or sold their land. Now those few left use air conditioned tractors the size of sheds to farm 2000 plus acres, and GMO seed (genetically modified organism) and chemicals make it possible to grow only one crop. Monsanto seems to have been given full reign to control seed, suing farmers whose organic seed becomes contaminated for impingement, as well as to suppress research showing the dangerous impact of the chemicals on the endocrine systems of living things, including humans, and on the larger environment. Corporations have even been able to suppress the identity of food that has genetically modified ingredients in it, now most of our processed foods in United States, denying the consumer the right to make his or her own decisions about consuming it. This is hardly grass-roots decision making!

To his dying day, my father bought what he was sold: not only the poisoned seed, which killed rodents and anything else that got into it, including my brother’s pig, not only the the GMO seed requiring expensive chemicals to grow, but also the belief that we had to farm this way or we could not feed the people in the world. By the 90’s small farmers like my father were no longer making the decisions about how to relate to our earth.

In 2002, my husband and I attended a trade show in Austin, Texas, All Things Organic. There were a number of small farm-based businesses there, including our own Biodynamic organic lavender business. I will never forget that conference, the excitement among the exhibitors, the common feeling of mission, and last, but not least, the keynote address, given by Robert Kennedy, Jr..

Kennedy is a tall, lithe attorney whose classrooms of students are responsible for some of the more important watchdog-inspired cleanups of our waterways. More recently his work has turned to the treatment of animals in so-called “industrial” settings. That day he as walked onto the stage, he rolled up his sleeves, and with tears in his eyes, thanked the small farmers there for doing what we were doing. He then went on to tell us why the belief that we can only feed the people of the world through large farms using industrial techniques was simply a distortion of the facts, perpetrated by corporations. He talked about the clean up factor of industrial meat farming, how it contaminates ground water, not to mention the inhumane treatment of the animals. Small farms are an economically viable way to raise food, he proclaimed, and in fact, the only sane way, particularly when you factor clean up cost now on the tax payer.

Farmers like my father were caught up in a collective tidal wave of proportions previously unknown, exploited by politicians through their belief that a hands-off government meant grass-roots control.

But Jesse’s generation is another matter. They are not so naive! Independent, yes, but not trusting in the powers that be in the way my father’s generation often was. Jesse has become a farmer, something I never imagined, though I should not be surprised! I recognize that spirit in him: the love of hard work, the willingness to accept the risks, that passion for the earth. (See my own story of return in Farming Soul: A Tale of Initiation) But I also see commitment in this group of farmers to true grass-roots action, giving meaning to that slogan, Think globally; act locally. Even in our independent action, we need to consider the impact on all. Otherwise, we can become pawns to larger forces. Perhaps farming’s phoenix is rising.

|

| Presented to our family farm in 1976. The farm’s future is in question. |