Piano Lessons

I wrote this several years ago, before the passing of both of my parents, a son’s wedding, and the birth of my first grandchild. Although I have yet to find the new teacher, I still love to practice.

| Music with Mrs. Russell’s Notes |

I was six when I had my first piano lesson. My mother picked me up after school, and we drove the fifteen miles to Decatur to Mrs. Russell’s home. Mrs. Russell seemed ancient to me. She wore black, high-heeled oxford shoes, the same style that my grandmothers wore, and long calico dresses of the vintage we do not see any more. I sat on her piano bench, she to my right in a straight backed chair. That first day I remember her exclaiming, “Oh, Patty!” –for that is what she called me, she and my grandmothers, only–“You have such lovely hands for playing the piano!” She examined the way that I held them at the key board. “Such good natural form!” I was a sucker for flattery, so our first lesson went well.

She gave me a red, elongated booklet whose sole purpose was to teach me the notes. The first “song” I played was “Middle C.” Mrs. Russell sang as she played. Her voice was thin and high pitched. She obviously had not had voice lessons. “I am C! Middle C! Left hand, Right hand! Middle C!” I was to practice it five times each day, which I diligently did.

My mother gave me five sheep from the nativity scene, and each time that I played a piece through, I moved one of the sheep from the left hand side of the piano to the right. By the time I was nine, I was counting sheep an hour a day.

Each lesson was a dollar and lasted half an hour. I enjoyed the lesson and I loved practicing, something that I kept as secret as the fact that I loved poetry. What I didn’t love was waiting for my lesson while Mrs. Russell was finishing with the student before me, or, later, when my younger sister was having her lesson, and then my brother. Mr. Russell sat out of sight in the dining room off the living room smoking cigars. Only occasionally did we actually see him, but there were always clouds of smoke hanging midair. Maybe it’s the only way he could tolerate those after school piano lessons.

Mrs. Russell thought I held promise and insisted that I participate in the yearly auditions. This involved perfecting a piece, committing it to memory, and then going before a judge at Millikin University in Decatur. My mother and I would sit in the dimly lit lobby until a grim, ageless woman carrying an alligator shoulder bag appeared to take me, alone, to the audition room where a judge sat a few yards away from a grand piano. I was to give the judge my music and then play my piece. I was graded on fingering, rhythm, quality of feeling, generally, how I executed the piece. At my next lesson Mrs.Russell had received a grade card, and we reviewed it. She seemed gratified with the results.

The other ordeal was the yearly recital. Again, we had to memorize a piece. My mother got me a new dress, and I wore a corsage. In the early years the recital was held in a large and formal room at the Decatur Women’s Club. Again, a grand piano was set up at one end with rows and rows of relatives facing us. We were to walk to the piano, play our piece, then curtsy or bow, depending on our gender. The youngest and most inexperienced players were the first on the program; the older, more accomplished, the last.

After some years of this, you realized that Mrs. Russell had favorite songs: “Let Us Chase the Squirrel,” “Skip to my Lou,” “Spinning Song,” “Aragonaise.” Every recital had practically the same program; there were just different players. One year I was playing the “Spinning Song” and within a year or so it would be my sister, although she did not like to practice, so it took her longer to move up the program. My brother didn’t make it much past “Let us Chase the Squirrel.”

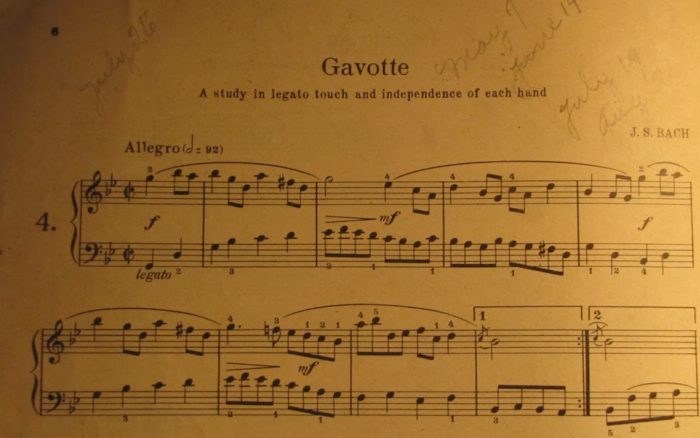

When I remember these lessons, I am surprised to realize how little I cared about pleasing Mrs. Russell. Maybe her expectations for performance were too much like my mother’s, and I simply had to distance myself. But I loved practicing. For an hour a day I was transported out of time. I studied Bach’s Gavottes, Polonaises, and Minuets, always five times a day, everyday of the week. I played my way through the birth of my youngest sister, my mother’s ongoing illnesses, my grandmother’s lingering death, and my brother’s diagnosis of a rare liver condition. The keyboard offered an expression of feeling that I could not verbalize: forzando, with force, loud. Legato, smooth and connected. Bach’s order consolidated my ego. Although at some point I quit counting sheep, I always played each piece five times.

The showdown came when I was sixteen. I was now the oldest and most accomplished student, the punctuation at the end of the recital. I did not want to play. My mother told me that I owed it to Mrs. Russell, that I had to.

I will never forget the evening. The recital was now held in a local music store after hours, and all the students were grouped in the back room where the sheet music was stored. Mrs. Russell not only expected me to play on the program with these youngsters (for at sixteen, I felt quite above it), but she also expected me to babysit during the recital, something that I had not agreed to do. Let’s just say, the kids were unruly, got into the sheet music, and I did nothing to stop it. Mrs. Russell was out listening, and when she returned, she exploded. What had I let them do?!!! I don’t remember how I felt, but I do remember I started “Aragonaise”, allegro brillante, on the wrong cord, and that I did not stop. I played the entire piece loud and with great force (ff ), but all in the wrong key, and missing notes. It was absolutely terrible. When I got up, I curtsied, and I never went back to a piano lesson again. In fact, I did not play the piano again, until last fall.

When I received a notice of a piano sale at a local college, I decided to just look. And, of course, there was this beautiful Yamaha grand, and it was a deal. It was also love at first sight. As I was signing the papers, I started to say, “I have been waiting for this for 36 years…” but I couldn’t finish the sentence. I was shocked by the rush of emotion. The piano movers were arriving about the same time I got home. We had to transfer the piano to a pickup truck to get it up to the house.

My left hand forgot everything; my right hand did a little better. I started at the bottom of the recital program. My mother happily sent me my old sheet music (“I can’t believe it! Finally! After all that money I spent on those lessons…”) First Lessons in Bach, “Spinning Song,” and, of course, “Aragonaise! “ I’m surprised how quickly I remember.

I’m also surprised how much I’m reminded of Mrs. Russell as I practice. There’s her writing penciled on the music. “Count aloud.” “Fingering.” Circles around “pp” (very softly). I remember how she had me play the hands separately on a new piece, but only briefly, before playing them together. I do that now. There’s her penciled check marking two lines to practice five times daily this week. The date: Jan 29, probably 1962. Her penciled numbers give fingering.

She’s helping me remember how to play. I still play each piece five times, and I still play because I love to. I’m catching up to where I left off. Now I’m playing through my mother’s diabetes complications, my father’s dizzy spells, my youngest son’s leaving home for college. Then I was moving through puberty; now I entertain menopause. Bach draws me some days; Chopin others. Soon I’ll be ready for a new teacher. This time, I’ll choose. It’s been late in coming, thirty six years late, but I feel gratitude for this woman who taught me to play the piano.