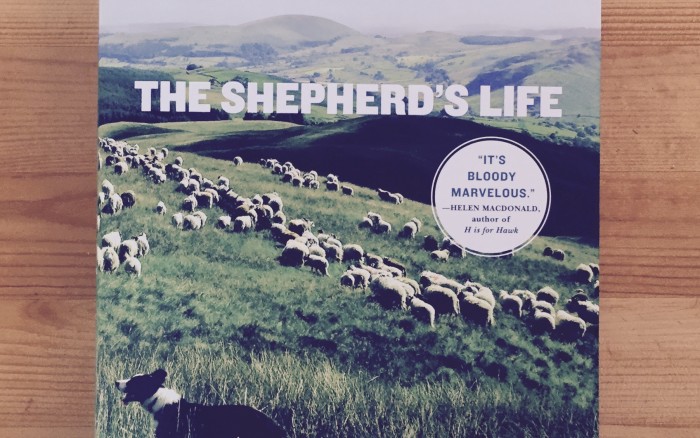

Books come when you need them. For me, The Shepherd’s Life: Modern Dispatches from an Ancient Landscape, by James Rebanks, is such a book. Rebanks is the descendent of an ancient generational lineage of shepherds in the Lake District of Northern England. He writes about his childhood growing up as the inheritor of the tradition of shepherding and about how he has grown to take up the modern challenges of the mantel himself. His writing is pithy yet descriptive, a story with a larger tale.

Much of the book is place-centered: the practices of being a shepherd, the taxing demands of the mountains, and the importance of the fabric of family and community. But it also depicts an archetypal pattern that has developed over the two centuries of major immigration. What happens to us when we move from place to place? What happens to our feeling about the land we live on? When my husband and I visited his mother’s family in Germany, we were told that another family was newcomers, they had only been there 300 years!

Rebanks knows his land, some of which is common land, something we do not understand in United States. “This is an ancient, hard-earned, local kind of freedom that was stolen from people elsewhere,” he writes of the commons and of shepherding. “The kind of freedom that the nineteenth-century peasant poet John Clare wrote about. He lamented the changes in the Northamptonshire landscape he loved because of the enclosure. He saw the disconnection that was being created between people like him and the land, something that has gotten worse with each passing year since then. … ours is a rooted and local kind of freedom tied to working common land, the freedom of the commoner, a community-based relationship with the land. By remaining in a place, working on it, and paying my dues, I am entitled to a share of its commonwealth (p.286).”

Contrast this to our current value of private property rights, a “right” that is beginning to be reconsidered in the drought and water issues in California. We are discovering that we are interconnected. Dwindling resources of land and water force the issue. The attitude of Rebanks of a serving a larger purpose is gone. “I have always liked the feeling of carrying on something bigger than me, something that stretches back through other hands and other eyes into the depths of time. To work there [in the mountains] is a humbling thing, the opposite of conquering a mountain…(p.286).

Does the concept of private property and of financial return on that private property, serve the ego’s agendas of self interests, and open space and the commons serve a larger, collective Self (C. G. Jung)? I suspect so. Certainly First People’s relationship with the earth was much more of that of the commons. When white man arrived, private property rights eclipsed territorial designations within the commons— and the environmental and social destruction began.

It is time we seriously rethink our relationship to land. The Shepherd’s Life is a stimulus and a guidebook in so doing, at once locally based with universal truths.