Living Here Together

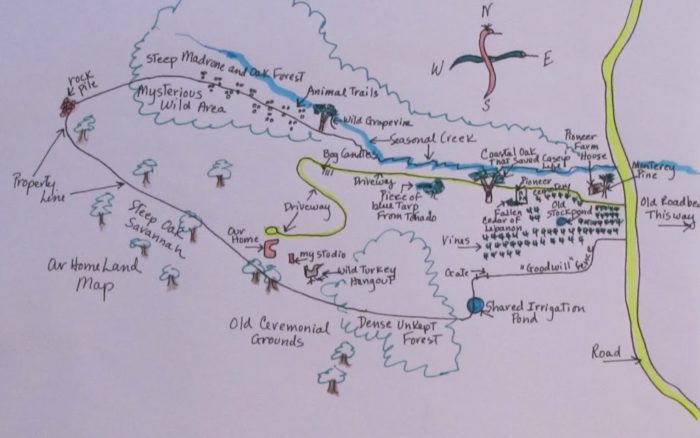

When we first walked the property line, we found a giant wild grape vine that hung from tall madrone trees along the creek, strong enough to swing on. Here are many animal trails we have followed over the years, pruning back poison oak and removing fallen branches to keep the trails clear. Finally the property line converges with a seasonal creek back to the road, weaving through giant bay trees and coastal oaks that gracefully stretch thick trunk-like branches across the creek. On one of these Ramon’s children built a tree house many years ago.

So encircled is the ranch I love, a ranch still graced with many native grasses and plants while also bearing scars of man’s carelessness or ignorance. In two places along these seasonal creeks we have found enormous piles of glass jars and cans dumped and partially buried. We have also found grinding stones and a rose quartz crystal the size of a human heart in the area of the vineyard sloping down to the creek. It is land we too inadvertently damaged through “improving” a wagon trail over the ridge to our own home. The hillside’s fragile soils along the road literally liquify in heavy winter rain, and we spend many hours walking the road, clearing the ditches of debris, lining vulnerable areas with rock.

Slowly we are learning the stories here, some small, some large. Where the bog candles bloom in June. Who lived here before us. How the old woman down the road, now dead, used to drink the water out of the stock pond. Who was buried in the pioneer cemetery in the middle of the property (one family buried 10 children whose graves are marked by redwood markers), and who wasn’t (Uncle Oscar, a drunk, buried outside the fence). How the road used to move differently through the east end of the property, leaving much more room in front of the old pioneer house. How the tall Monterey Pine that drops so many needles by the front porch of that house was planted the day the owner’s daughter was born. The coastal oak by the creek that kept my then 16 year old son from rolling the car when he sped down the long slippery driveway within the first week he had his license. The speck of blue canvas still hanging in the tree along the vineyard left from the small tornado that also impaled a rowboat on a grape trellis and uprooted a Cedar of Lebanon in the cemetery, the tornado my husband and I watched trace the northern boundary of our property from our housing site when we were building our home 14 years ago.

These are stories of our history here, as well as the history of who was here before us, the land being the constant. When we tell the stories, we re-member ourselves into the earth of this locale. But maybe the stories go a step further as well. Ecological philosopher David Abram claims we cannot “restore the land without restorying [italics mine] the land.”

When stories are no longer being told in the woods or along the banks of rivers– when the land is no longer being honored, ALOUD!, as an animate, expressive power- then the human senses lose their attunement to the surrounding terrain. We no longer feel the particular pulse of our place… . Increasingly blind and deaf, increasingly impervious to the sensuous world, the technological mind begins to lay waste to the earth. “Storytelling and Wonder: On the Rejuvenation of Oral Culture,” by David Abram, Ph.D.

Through the storytelling of the land on which we live, we knit ourselves into the fabric of it: the earth, the trees, the animals. In so doing, we become sensitized—again!— to what is also non-human and very alive. The coastal oak along the driveway that saved my son is a friend I greet daily as I pass with our goats (each a story in herself!) And I find myself asking that mountainous slope as we pass along the gravel driveway, What can we do to repair what we have done to you? In that quiet I hear the chattering of a bird disturbed by our proximity to her nest. Okay. We will move on. And we do, with increased awareness of the aliveness of the hillside and its many inhabitants, ourselves included, all of us living here together.